21st July 2023

The importance of transition pathways to net zero: part 1 – the Government

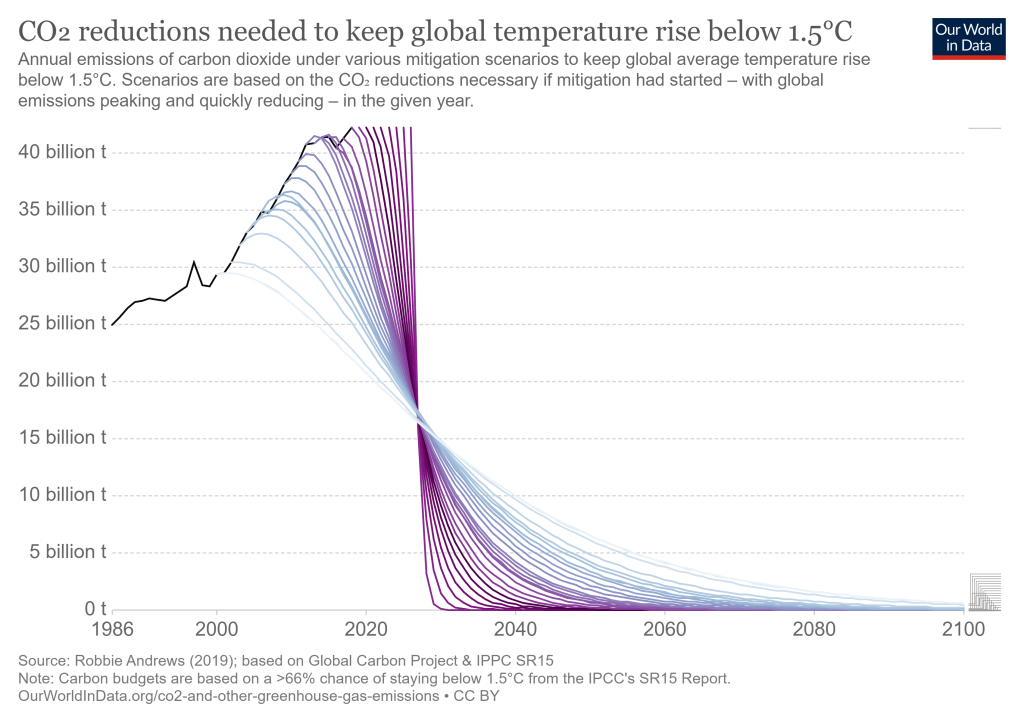

The spread of extreme heat waves across the globe only reinforces the urgency that surrounds climate action. These extreme temperatures which are affecting both land and sea are a result of greenhouse gases we have already released into the atmosphere. These extreme weather events are here to stay, and if we do not curb emissions, their frequency and intensity will increase. If life on earth is to remain tolerably liveable, then we must reach both the halving of emissions by 2030 and the 2050 net zero target, as established in the 2015 Paris Agreement. All nations who are signatories to the Agreement are expected to deliver. As part of that process there need to be transition plans or route maps or in the case of the UK, Carbon Budgets, that detail how to get from here to there.

In the UK the 2008 Climate Change Act set up the Climate Change Committee which is tasked with producing five yearly carbon budgets for the Government, and with producing an annual progress report. The budget as presented as advice for the Government to review and enshrine in law. So far all the CCC’s recommendations have been followed. The first three budgets (for 2008-23) were set in 2008 and the fourth (for 2023-27) in 2011. NB The twelve year lead in period is there to give those making investments time to respond. The fifth carbon budget was set in 2016. The original 2008 target was an overall cut in greenhouse gas emissions of at least 80 per cent by 2050, relative to 1990. However, in 2019 this was replaced with a target of achieving net zero emissions by 2050 and this is reflected in the more exacting sixth carbon budget issued in 2020. (https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/what-are-carbon-budgets-and-why-do-we-have-them/)

Currently then, we in the UK are embarking on the era of the Fourth Carbon Budget. At the same time we should be seeing investment already in place for the Fifth Carbon budget, as well as seeing new investment policies being put in place to meet the Sixth Carbon Budget. At anyone time the UK should be benefitting from emissions reductions arising from the current Budget, investing in the infrastructure for the next Budget/s, and developing policies to implement these Budgets.

To date the targets of all of the first three Carbon Budgets have been met. In part this was due to a reduction of economic activity over the period (most notably during the covid pandemic) coupled with rising fuel prices which depressed demand (again largely influenced by external factors such as the war in Ukraine). The pandemic has contributed a further plus factor in changing the commuting patterns and lowering to small degree traffic levels. In addition a number of the winters have been warmer than expected.

Meeting these targets has also been eased by a global shift towards renewable energy (sparked by the worries of oil running out and the ever increasing cost of oil and gas) and by a similarly motivated shift towards more energy efficient appliances and equipment (including more energy efficient vehicles). Hereon success in meeting future targets will rely far more on the skill with which forward thinking investments and comprehensive plans have been implemented over the last decade or more to attain these targets. Transitioning to a world where, for example, all energy comes from renewable sources, where every home functions like a passive house, where active travel is the norm and public transport provides a comprehensive service, does not happen overnight. It needs advance planning and investment. If energy is to come from renewable sources then wind farms needed to built. If homes are to upgraded to passive house standard, then a workforce is needed to install insulation and triple glazing. If active travel is to increase then safe cycle and pedestrian routes need to be put in place with nighttime lighting. If the public transport network is to be comprehensive, more bus routes need to be open up, buses bought and staff recruited. To achieve the transition we need, we are reliant on both the Government and business leaders.

Each year the CCC provides Parliament with a Progress Report. In the introduction to this year’s, Lord Deben wrote: “In this report, we comment on a curious situation. This year, the Government has published more detail on their climate programme than ever before, cajoled to do so by the Courts. But Ministers seem less willing to put that programme at the centre of their stated aims. Our confidence in the achievement of the UK’s 2030 target and the Fifth and Sixth Carbon Budgets has markedly declined from last year.” https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Progress-in-reducing-UK-emissions-2023-Report-to-Parliament.pdf

This is concern is echoed throughout the report, for example: “However our confidence in the UK meeting the 2030 NDC [‘nationally determined contribution’ being each nation’s contribution to reducing global emissions in line with the Paris Agreement] and the Sixth Carbon Budget (2033-2037) has decreased since last year … whilst we would expect policies to be less developed for targets further away in time, the NDC is now only seven years away.”

The Report (pages 2, 28 & 31) lists the areas where the Government’s lack of planning and investment is materially affecting the chances of meeting the targets of Sixth Carbon Budget. For example:

- Land use – the Government needs to formulate a policy framework, and there needs to be an urgent scaling up of land use mitigation measures such as tree planting and peatland restoration.

- Buildings – rapid pursuit of zero carbon standards for new builds, and energy efficiency improvements for existing buildings.

- Electricity – a commitment to the Government’s own plans to decarbonise the electric supply system by 2030 (giving confidence to would-be investors) and a rebalancing of the relative costs of gas and electricity.

- Just transition – using fiscal and policy levers to ensure low-carbon choices are an affordable option for everyone.

- Green workforce – this needs to be grown; a commitment to the green economy would be a string signal to the private sector.

- Waste – greater emphasis needs to be given to waste prevention; equally reliance should not be placed on using waste as a source of energy.

- Industrial emissions – these need to be reduced by 69% by 2035 relative to 2022. Government needs to be do more to accelerate decarbonisation- eg through accelerating the electrification of industrial heat (blast furnaces and similar).

- Aviation – no new airport expansion.

- Fossil fuels – no new oil and gas without stringent tests; presumption against coal.

This week as I was sat outside Parliament as part of the Earth Vigil, I was questioned, ‘What was it that we were asking of the Government’? A good question to which the simplest answer might be to do what it’s advisers, The Climate Change Committee, recommends.