14th January 2026

Approximately 12% (47.7 MtCO2e as of 2022) of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions come from farming. Of that 58% is methane from livestock, a further 28% is nitrous oxides from fertilisers etc and 16% CO2 from motor vehicles etc. (1). Agriculture therefore has a significant part to play in reducing the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions to net zero. To achieve this changes – a transition – in agricultural methods and in the balance between livestock and arable land farming, and between food production and enabling the land to contribute in other ways to the maintenance of a healthy environment, will be necessary. This is noted in the SRUC report submitted in support of the UK’s 7th carbon budget: “The increasing need to reduce agricultural and food related emissions underlines the importance of estimating the mitigation potential in agricultural production in the wider context of emission reductions achievable with changing dietary patterns, land use and the agricultural production mix.” (2)

As the UK moves to a net zero economy, it is obvious that emissions from agriculture need to be reduced – the Climate Change Committee’s target is 21 MtCO2 by 2050. (Agriculture – including deliberate none cultivation of the land – offers opportunities to increase natural carbon absorption which should more than offset this remaining 21Mt of CO2). Every five years the CCC produces a carbon budget. The budget for the current period is the fourth carbon budget (2023-2027). The fifth carbon budget (2028-2032) was approved in 2016. The sixth carbon budget (2033-2037) whilst an amended version was initially approved by government, it was challenged in the courts as being insufficient and a revised budget submitted by the government in October 2025. The seventh carbon budget (2028-2042) was submitted by the CCC in 2025 for review and an agreed version should be ready approval by Parliament in June 2026.

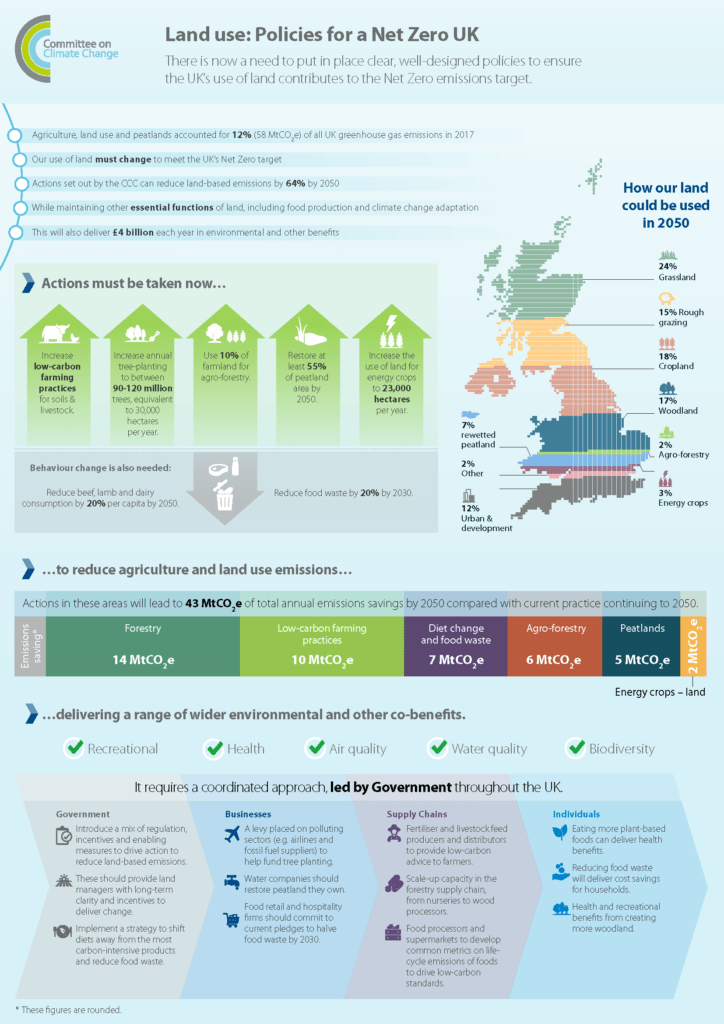

The following infographic dates from 2020 and was produced by the CCC as part of their report, Land use: Policies for a Net Zero UK, which explored how policies could be implemented vis a vis agriculture to achieve the 2050 net zero target. It is gives useful overview of what changes will – are – being required of the agricultural sector. (3)

(NB the updated Land Use Framework (LUF) is still be worked on and is already at least a year late! This policy document won’t per-se specify what land should be used for what but will encourage informed decisions that hopefully produce a win-win solution where there are competing demands -eg food production and housing, nature restoration and new infrastructure. (4))

The seventh budget forecasts that emissions from agriculture should fall to 29.2 MtCO2e by 2040 to 26.4 MtCO2e by 2050 at which point this sum will be balanced by the land-based carbon sequestration which will have been increasing year on year as the impact of planting more trees, restoring peatlands etc takes effect.

The budget envisages a reduction in numbers of livestock, releasing land for growing other uses – eg horticulture, woodlands, and bio-energy crops (for use as a short term transition fuel) etc. This also envisages a reduction in consumption of meat and dairy products by consumers. There is no specific mention of growing beans and pulses but this would be essential to provide a sustainable plant based alternative to meat and dairy products.

The budget also envisages an increase in woodlands (mix of broadleaf and coniferous trees) to cover 16% of the UK, as well as year on year increase in agroforestry (this is still novel in the UK). To meet sequestration targets much of this tree planting needs to happen by 2030. The budget also relies on a 40% increase in hedgerows by 2050 as another boost for carbon sequestration and for biodiversity.

The budget envisages rewetting and restoring both upland and lowland peatlands – 3% of the latter by 2040 and 56% by 2050. Again this adaptation needs to implemented sooner rather than later to maximise the benefits of carbon sequestration. This critical adaptation will include rewetting significant areas of peatlands in East Anglia currently used for growing vegetables. Alternative areas of the country would have to be developed for vegetable growing. The budget also envisages 10% of horticulture will be taking place under glass by 2050.

The budget recognises that farmers will need financial support as they negotiate this transition. It will be important that farmers have longer term certainty as regards these changes and the support they will receive.

Government policies also need to promote the switch by consumers from meat and dairy to plant based alternatives. This could promote the health benefits of eating a richer plant-based diet.

As part of the process of producing the seventh carbon budget, the CCC convened a citizens’ panel to explore how these changes would impact households. It was generally accepted that there was a need to make changes in diet with the proviso that information should be made available showing the different impacts of alternative foods. The panel favoured a shift to healthier, home cooked foods and envisages that education could play a role in enabling plant-based meal preparation. There was agreement that plant-based foods needed to be competitively priced compared with alternatives – especially for those on low incomes. This is something that may require government directives for the food industry – especially as many of the panelist’s were uneasy about replacing meat and dairy with highly processed options such as precision fermentation. The panel was also concerned that policies should ensure the proper remuneration of farmers.

To read either a summary of the seventh carbon budget or the full report see :-

Further reading – https://www.sustainweb.org/news/feb25-seventh-carbon-budget-climate-change-committee/

However how is this transition to be financed or effected?

(1) https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/agri-climate-report-2024/agri-climate-report-2024

(3) https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/land-use-policies-for-a-net-zero-uk/