23rd September 2022

If we all went vegan what would happen to all the cows?

This seems to be a frequent concern amongst those who are not vegan. If people didn’t eat meat or drink milk, would cows become extinct?

The question is one of genuine concern but raises some other questions in response. For example what life does a cow have? Dairy cows will commence their milking life aged 2 when their first calf will be removed from her care within hours of birth. She will then give birth once year, being milked for ten months producing quantities of milk (on average 8000 litres) greatly in excess of what a calf would consume. After 2.5 -4 years, when her milking yields drop, she will be slaughtered. The usual life expectancy of a cow is 20 years. Of her offspring, males calves will have a limited life to be slaughtered as veal at 5 – 7 months. Of her female calves most will follow in this mother’s footsteps unless they are deformed or ill, in which case they too will be slaughtered.

Very few farmed cattle enjoy a full life. By contrast cattle kept on re-wilded land, although smaller in number, live a much more natural life. In the Lake District re-wilding projects are in place at Haweswater, Ennerdale and the Lowther Estate, whilst in Sussex there is the now famous Knepp Estate. According to Rewilding Britain 112,166 hectares of land are now part of a re-wilding project.

So no, cows would not become extinct but would be kept in much smaller numbers – just as rare breeds of many farm animals are being conserved.

In 2020 there were 9.36 million head of cattle in the UK. It was not always so! Originally there were only the early forebears of cattle, the aurochs. Overtime cattle were domesticated and as the human population of the UK grew so did the number of cattle. Selective breeding improved and diversified the cattle with some favoured for milk production and others for meat. As the human and domestic animal populations increased, so the amount of uncultivated land and wildlife decreased: the auroch was hunted to extinction in the UK about 3000 years ago; the brown bear became extinct in the 6th century whilst the wolf hung on until the 17th century. What is true for the UK is also true world wide. Whilst once humans and domesticated animals were once nonexistent, they now comprise 36% and 60% of the biomass of all mammals, leaving just 4% as wild animals (biomass measures the quantity of a species by its mass rather than its numerical quantity).

Rather than it being a question of ‘what would happen to all the cows?’ perhaps the question should be ‘what has happened to all the wild animals?’ The State of Nature Report of 2019noted that since the 1970s, 41% of UK wildlife has declined, and that 26% of the UK’s mammals are at risk of becoming extinct. Re-wilding more of our land would help reverse this decline and allow for the reintroduction of lost species such as the lynx and the stork.

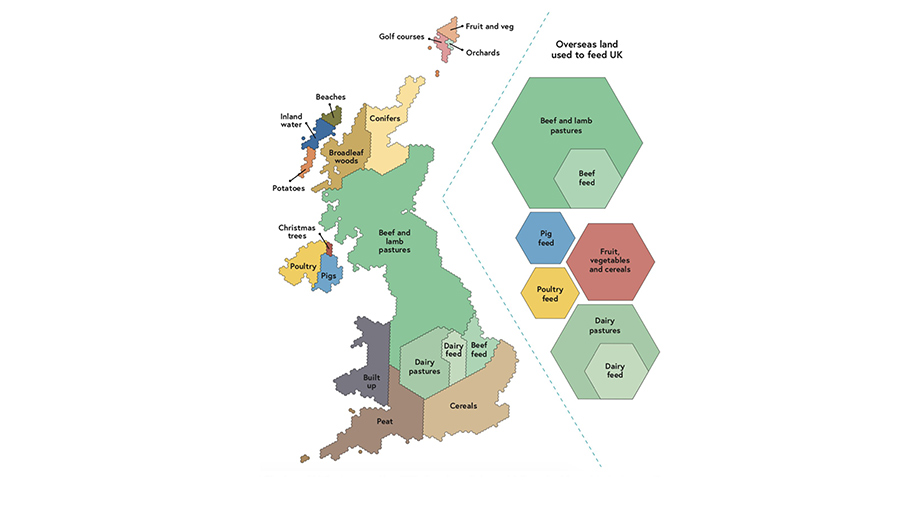

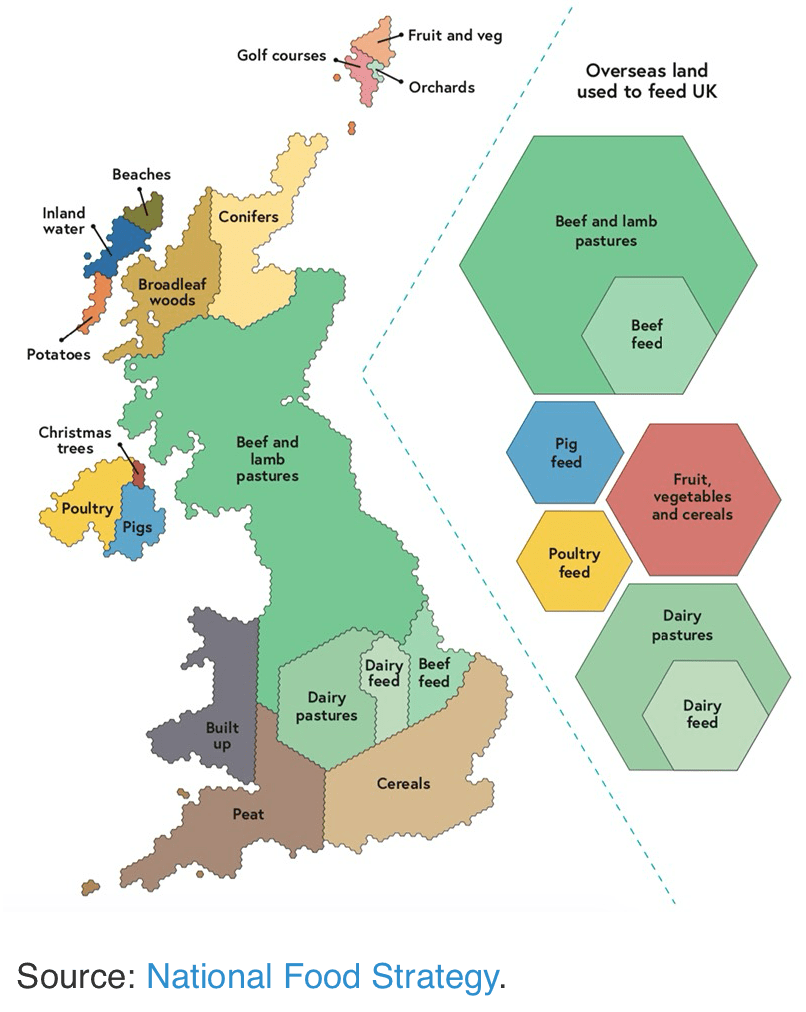

Globally 77% of agricultural land is used to feed livestock, including both grazing land and the land used to grow animal feed. In the UK 40% of the land (9.74 million hectares) comprisespermanent grazing, 6% temporary grazing (1 – 5 years) and 5% rough grazing. Only 20% of the land is used for arable crops. Even so home grown animal feed is supplemented by imports – somewhere in the region of 50%.

Globally the 77% of land used for grazing and feeding farm animals, produces only 18% of the world’s food calories. At the same time this major land use contributes more than half of the carbon footprint of our global food production. If everyone globally were to eat the same amount of meat as the average British person (approx 85g per day), then the amount of farm land needed would have to increase – putting even more pressure on natural habitats and wildlife. And if everyone were to eat as much meat as the average American, we would run out of land.

Reducing our consumption of meat and dairy products would release more arable land for growing more sustainably a great variety of plant-based proteins with the potential to improve the diets and health of billions of people world wide (subject to a radical improvement of trade and wealth distribution systems). Research the by the UN suggests that with fewer cases of lower coronary heart disease, strokes, type 2 diabetes and some cancers, a global vegan diet would also result in 8.1 million fewer deaths per year worldwide.

Britons have in fact already reduced their meat consumption by 17% over the last decade. The Government’s Food Strategy has the target of reducing that by 30% by 2030. This target has been set in recognition of the adverse affect meat production has on both climate change and the environment, as well as the link between the consumption of red and processed meat the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and certain types of cancer.

Looking to the future, there will be fewer cows – but hopefully they will be enjoying a happier life – and instead more land used to restore greater biodiversity.

Further reading