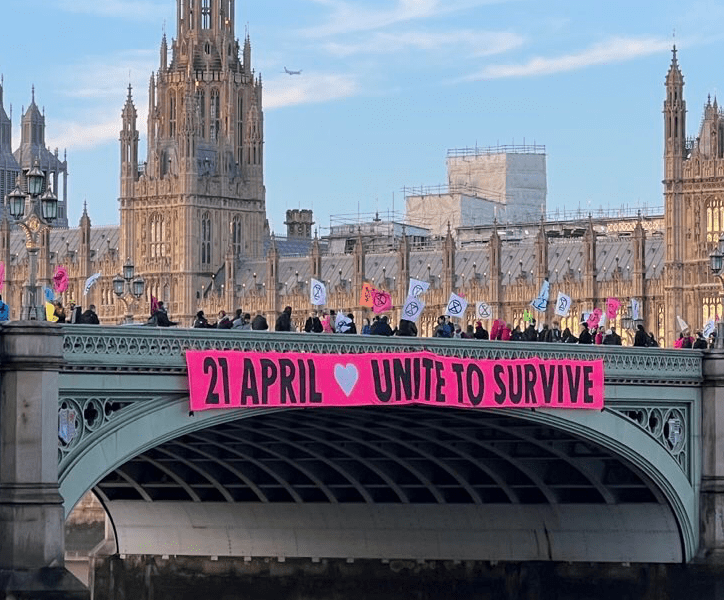

20th January 2023

Imagining life in 2033

By 2033 we should be at least half way to net zero. How will things have changed? What will daily life look like? Imagine a letter from the future …

In many ways life in 2033 is not that different from in 2023. I still live in the same house, with the same husband and even the same – now rather elderly – cat. We have recently replaced the solar panels on our roof and are now not just self sufficient for energy but are regularly put electricity back into the grid. Talking of solar panels, every house in our street now has them, as does the local school and our church – and you have probably guessed, very few buildings now-a-days have gas boilers.

Other changes in our street include more trees, which provide welcome shade during heat waves, and fewer cars. Being an affluent area, most people have hung into their electric cars despite the rising ULEZ charge, but as in most urban areas many more journeys are now made by cycle or public transport. All main roads now have a dedicated cycle track wide enough for cargo and family bikes. Buses and suburban trains have all been free for the last five years leading to less cars using the roads and, therefore, faster journey times for buses! Suburban trains run on a regular ten minute interval and trains on the mainlines operate on a ‘Taktfahrplan’ similar to the Swiss one, ensuring good connections on all routes. Most people opt for the half price rail card, especially families as children travel free.

Another change you might notice is the number of cargo cycles. They were certainly around in 2023 but the exception rather than the rule. Increases in road tax in 2025 saw a rapid expansion of delivery bikes, and electric ones regularly use the vehicle lane on the main roads where they can move at the same speed as other users – oh yes, I should have pointed out that in London the speed limit is now 20mph on all roads. The NHS has certainly benefited from the upswing in cycling. It has made us fitter and the reduced particulate pollution from tyres and brakes has helped reduce breathing problems. There is talk now of replacing buses with trams.

You will be pleased to hear that we do still have a national health service. There were some dodgy moments when it looked like the system might collapse, but with the influence of a people’s assembly, the whole health and welfare system is being overhauled. There is a focus on preventative care and long term investment plan – improving the health of children (physical, mental and educational) will have profound benefits for our society but the financial savings may take 20 to 30 years to kick in.

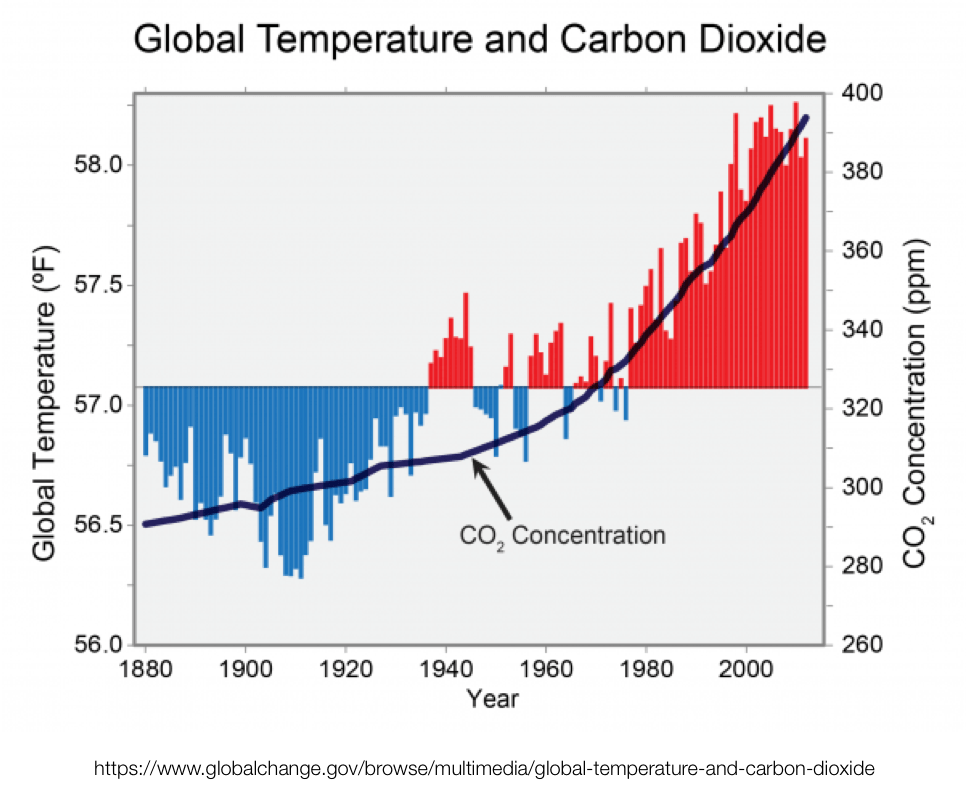

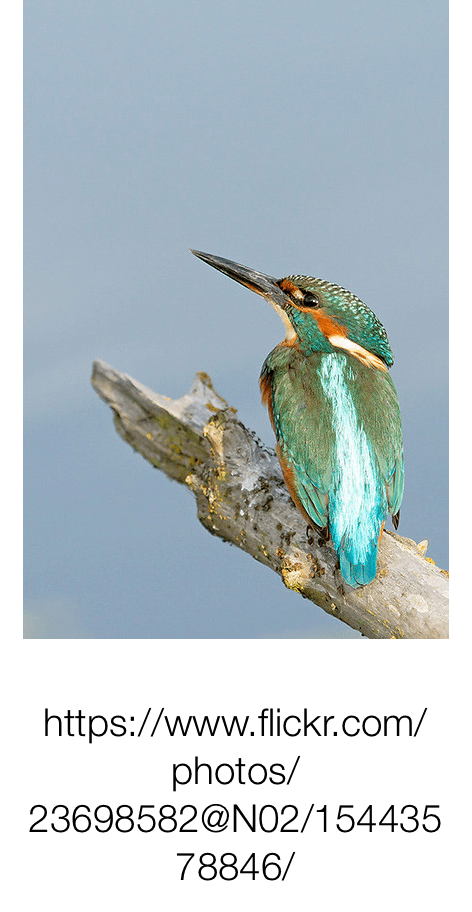

It has been surprising how much addressing the climate crisis has actually improved people’s wellbeing. All school and institutional meals are now all plant based, and I hope you are not surprised to hear that plant based dishes now occupy at least 50% of all restaurant menus. Vegan cooking is now mainstream although at the time the All Vegan Bake Off series in 2024 seemed radical. The change in our diets has not only improved our health but has changed the appearance of the rural landscape. With fewer livestock, those that are kept have a much higher welfare standard. And you will find that many farms and some of the larger rural homes keep a couple of sheep or pigs as outdoor pets. The UK is now self sufficient in growing wheat, whilst other arable land has been given over to growing a vast number of different fruits and vegetables. It has been a horticultural revolution with drip feed irrigation and small robots and drones making the work less back breaking. Work in this sector is now well paid and popular. Orchards have expanded and now encompass new trees such as olives, walnuts, pistachios and almonds, and are often intercropped with shade loving crops. The amount of trees in the landscape is perhaps the biggest change that you would notice. Not only have we seen orchards expand, but many areas have been rewilded with wide hedgerows, copses and new woodlands. The latest nature report has shown an increase in biodiversity in the UK. It is a revival that has had to be worked at but is now reaping rewards. Nightingales are now often recorded – but not necessarily in Berkeley Square! – and a new generation of children are listening out for the cuckoos in spring. Walks and trips to wildlife hides are increasingly popular as there is now so much more wildlife to see!

The Upper Richmond Road is still our main shopping area but it does look more attractive with more trees and well-stocked planters. If you want a few herbs, it’s a case of pick your own. I was going to say the traffic moves more slowly as back in 2023 the speed limit was 30mph. But now-a-days the traffic moves at a pretty constant 20mph which I’m sure is faster than it was then. I can remember sitting in the Artisan cafe watching the traffic remain stationary as the lights went from red to green and back to red. Traffic lanes are narrower now to make space for the cycle lanes. Milestone Green has finally been revamped (that’s been at least ten years in the planning) with new seating, a water feature and a large chess board.

There are a few different shops, such as The Splash – a bike wash coffee shop where customers enjoy a coffee and cake whilst their bike is cleaned, oil and tyres pumped. There’s the now standard repair shop, Repairs are Us, where can get virtual anything domestic repaired, and next to the Fara charity shop, is Tailor Tricks where they readjust any clothes you buy at Fara (or elsewhere) to fit. If you like a skirt but is too long or trousers that are too wide, they speedily make the adjustments. At the other end of the market is the made to measure fashion outlet. Video loops from the latest catwalks plus magazines and fabric swatches all entice you to try something new. Interactive screens show you what you would look like in these garments, and once you have made your choice, the workshop sets to work and within hours your made to measure outfit is ready.

Of course there are more cycle shops – and cycle accessory shops. The pet shops still thrive as we are increasingly aware of the value of pets for our mental wellbeing. Another growth has been in plant shops as we increasingly enjoy filling our homes with living things – as well as a growth in companies offering plant care services. Sheen also has its own coffee roastery, brewery, two new bakeries and a nut-cheese delicatessen. The local council has made a real effort to promote local businesses with preferential rates for local businesses.

Packaging has definitely changed. Initially it was the ending of single use plastic cups and boxes in 2023 that stimulated change. As suppliers adapted the packaging they produced, so supermarkets adopted this same packaging for ready meals, salads and pre-packed fruit. A year later reverse vending machines for bottles became obligatory – in supermarkets initially but quickly afterwards in all shops selling bottled goods. This included both glass and reusable plastic bottles, glass jars and reusable yogurt pots. All single use packaging is now either recyclable or compostable. The effect on refuse and recycling services has been marked. With less to throw into dustbins and recycling bins, most weekly collections have been replaced by fortnightly ones – a useful cost saving for councils.

As we have adapted to more extreme weather conditions so we have been adapting our buildings. Awnings that pull out are popular for both shops, houses and flats to provide shade in the summer but there can be problems if these are not safely retracted in advance of strong winds. The met office app usually provides adequate advance warning. Shops tend to have more substantial affairs that also provide protection from the rain. Keeping customers dry is a definite plus for trade!

Overhead there are far fewer airplanes – you might recall from the first covid lock down how surprised we were when the planes stopped and we could hear birds singing. Well that’s what we have now on a daily basis. There is a heavy tax to be paid for air flights (although there is an annual tax allowance that can put towards long haul flights). Air freight is gradually being replaced by rail freight and marine cargo vessels. Some capacity in the system has been freed up as we are no longer shipping oil, gas and coal around the world, and there has also been a sharp decline in the amount of animal feed and meat being shipped. Increasingly popular are cargo ships linking up with educational packages. You can take a ten day crossing over the Atlantic and use the time to engage in a fully immersive language course, learn to play bridge, or do a page to stage theatre production.

Ten years on things have changed but it is not a totally different world nor a life lacking in comfort. If anything we have a healthier and happier lifestyle.